‘Making A Difference’ – Interview with Mabuhay Magazine

01.11.2018

“I’M NOT A FASHION DESIGNER,” PASSAWEE KODAKA SAYS WITH A GRAVITY THAT SEEMS

to belie the fact that she founded a brand that produces decidedly wearable coats, blouses, trousers, shawls and bags – on the face of it, a fashion brand. To Passawee, however, Folkcharm’s fashion is secondary in the big picture. “Folkcharm is about preserving a traditional way of life while making it relevant. It’s not that I wanted to make clothes; clothes are just something that people use every day.” While her studio-showroom in the Bang Kapi district displays the label’s latest looks minimalist white, beige and blue cotton goods hanging from repurposed wooden shelves and bamboo rods, a layout inspired by the architecture of homes in the provinces – Passawee isn’t interested in being the next big thing on Bangkok’s runways. She has different dreams. With Folkcharm, she is at the vanguard of a movement that is proving sustainability can be more than a buzzword in Thailand.

Folkcharm works with local clothworkers, all women, who create apparel and accessories with Passawee and her colleagues. Some are home- based weavers and farmers living in rural villages in Loei, an arrowhead-shaped province that borders Laos; others attend a vocational training center in Bang Kapi before working. More than half of the sales made go back to all makers. However, Folkcharm’s concept does much more than what that economic model suggests. Passawee is trying to prove to younger generations that traditional crafts are worthwhile, that they don’t have to look to the bright lights of Bangkok to make money. In doing so, she hopes they will see the value of these disappearing arts. “The older generations used to teach the young how to weave,” says Passawee, who is impeccably dressed. She speaks with poised confidence and has a presence that a motley crew could rally around. “If girls didn’t know how to weave, men wouldn’t marry them because they didn’t know how to take care of their household. It was a social requirement. This current generation, or the generation before this, doesn’t know how to weave because there’s no need. Everyone buys 99-baht T-shirts.”

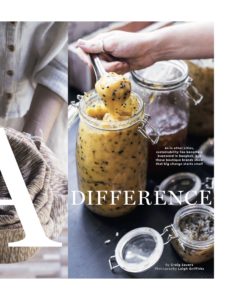

Since 2015, Folkcharm has grown its network of weavers from five to 30, and the women have seen their profits grow by more than 30%. Folkcharm’s impact has grown, too. “We kind of co-design products together and try to get them to do things that are out of their comfort zone while honing the skills they have,” Passawee says. Giving home-based women workers more opportunities has helped increase their decision-making power, she says, by decreasing their dependence on their husbands. The brand has also embraced an eco- conscious ethos. On top of using chemical-free cotton, all the offcuts are made into bags and accessories. And Folkcharm has even helped fill the gap in storytelling that would otherwise enhance the marketability of rural development projects.

In fact, the brand has recently started taking consumers to Loei. There, villagers teach them the 12 steps to making hand-spun, hand-woven cotton. “We’re trying to immerse consumers in the story rather than have them just buying products,” Passawee says. “People have to become more aware if we want to be sustainable. At the end of the day, it has to be a movement. It can’t just be Folkcharm.”

Story: Craig Sauers

Photography: Leigh Griffiths